It’s a little hard to believe it’s been a week.

As it turns out the street outside our hotel seems to be pretty popular with young Viennese folk; late into the night we heard them drinking with quite a bit of enthusiasm. You wouldn’t necessarily know it by morning, though. When I woke up (far too early, in my opinion) it was just me and the fan and, eventually, the sedate rumbling of streetcars.

For the first time in my life I have taken advantage of a hotel’s laundry service, carefully layering clothes into a little pink bakery bag (they were out of whatever they normally use) and carefully presenting it to the fellow at the front desk. 10 euros, and we get clean clothes for the rest of the trip. Trying not to feel too much like I am being a posh git, even as I carefully try to dress up slightly for reasons that will be evident later.

Our first stop today is the Kunsthistorisches Museum – very literally, the art history museum.  This beautiful building frames the Maria-Theresienplatz, facing its opposite number the natural history museum. (The Venus of Willendorf, apparently, lives there, though we won’t have time to swing by for a visit unfortunately.)

The interior of the building is as grand as the outside; it looks as though the Habsburgs felt their art collection deserved a suitably grand setting. I mean. Look at these stairs:

The production values inside the exhibits are quite something, too. Check out the staging on some of these:

Here is where I have to admit that we didn’t make it through the entire place. Not that it’s not worth it, I’m sure…but there is quite a lot of Stuff on display.

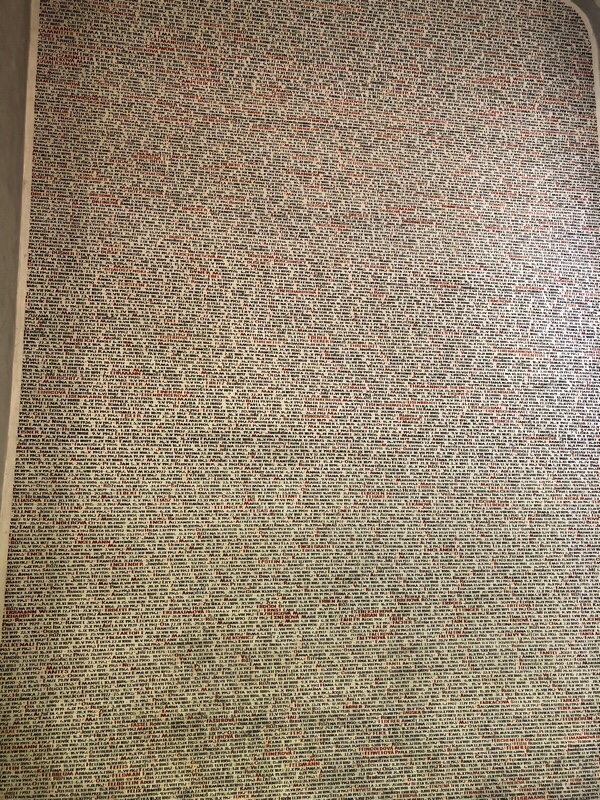

I do not know what it is that drives imperial-type folks to hoard massive collections of art and sculpture and artifacts. It’s certainly remarkable to see so much of it in one place. It’s…also remarkable how often the audio tour seemed to mention that such and such an artifact had been sent back to its homeland in Place. Perhaps there is a little guilt, after all the hoarding?

On the other hand, it is partly thanks to that hoarding that we’re able to see some of these things today. Like all those stories of how the original glass/paintings/carpets/manuscripts/what have you only survived the war because some enterprising person hid them in a basement somewhere, perhaps in a crate marked “Salt Pork” or something. (Not, obviously, a story we actually heard, though kind of an aggregate of many we heard on this trip.)

It’s simultaneously a bit romantic and a bit sad. Intrepid archivists or concerned citizens or a desperate mayor; the idea that somewhere out there in an unassuming attic there might still linger someone’s masterwork, waiting to be brought back out for someone to love it again.

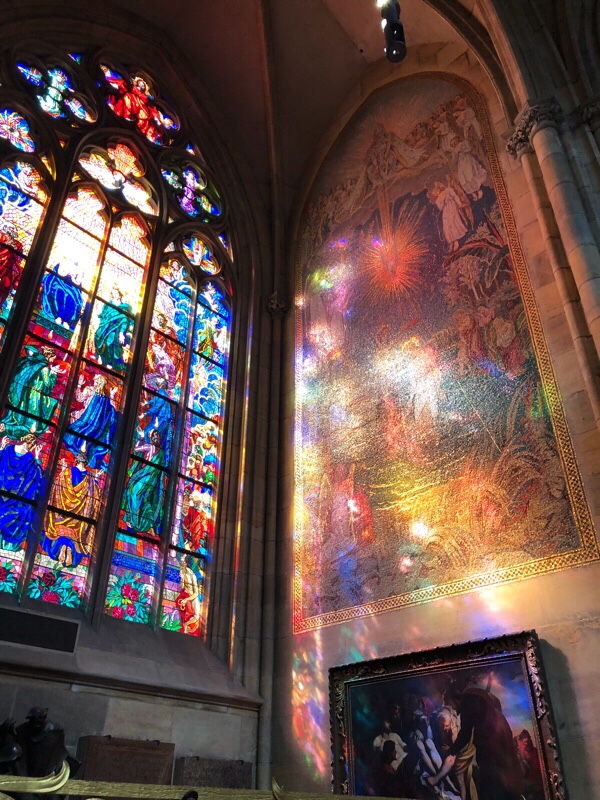

Interestingly, the museum seems to have some similarly conflicted ideas about itself. Their special exhibition at the moment is “The Shape of Time,” which sounds rather like an episode of Doctor Who but is actually a sort of…statement of self-awareness.

What do I mean? Well…As I’ve said, the museum has a pretty spectacular collection. A roomful of Caravaggios. Another that seems like it kind of contains every Breughel I can think of. You very literally cannot turn around, it seems, without smacking into something famous you’ve seen in art history books, except that here it is real and displayed in grand, high-ceilinged galleries with thoughtfully-arranged benches where earnest art students cluster to hone their craft. (And weary tourists like me jump at the chance to rest aching feet and take it all in while listening to the thoughtful English commentary.)

But here’s the thing: Almost none of what’s here is new. The collection is grand and full of beautiful things, but crystallized at a point before the Impressionists were around to do their thing, before we began cultivating mixed media, before photography and Banksy and mashups. And that’s sort of what’s behind “The Shape of Time.” We view art differently based on its context – and context is what this exhibition’s about, pairing old art with new in ways that are as much about our experience of what is around the art as the art itself.

Here’s one pairing, for example: Rembrandt was apparently mightily fond of painting his son Titus. In a dimly-lit gallery, one of these portraits hangs. Turn right, and you have a work of video art by Fiona Tan – “Nellie,” in which Rembrandt’s daughter Cornelia lingers restlessly in a sticky, humid room, underscored by the vague, jungly drones of insects. Titus looks sort of quietly heroic, gazing off into a bolder future; Cornelia writes a letter, gazes out a window, tosses uneasily in her sleep.  Somewhere hanging in the dimness between them one can feel the comment on gender roles.

Another dark room, another dark pairing: Steve McQueen points a video camera at a dying former racehorse, Running Thunder, the painful immediacy of the death of a lovely and powerful creature juxtaposed with what at first appears to be a fairly dull Brueghel vase of flowers. But, as the curator informs us, the flowers shown here do not share a season; this painting would be literally impossible. Celebration of life? Celebration of transience? How does it feel to observe inevitability and impossibility together?

A sculpture of lovers’ faces bent toward one another, close and affectionate, paired with Felix Gonzales-Torres’s “Perfect Lovers” – a set of two ordinary office clocks, set to the same time and left to run down. Already their times are not quite the same; one of them will inevitably “die” first, leaving the other alone. It’s a poignant image, made more so when you know that the artist paired these clocks while his own lover was dying of AIDS. He was the one left alone, in the end, though he passed away not long after.

Around another corner, in another room, medieval saints weep chastely over the crucified Jesus, unaware they now share a room with the broad white plinth containing Ron Mueck’s “Dead Dad,” a scaled-down representation of the body of his own father that is both eerily lifelike and a real punch in the guts for anyone who has ever beheld the body of someone they once loved without a life in it.

A classical sculpture of Aphrodite, someone’s long-ago image of perfect beauty, is displayed next to Eleanor Antin’s “Carvings,” a series of photographs, one a day in several different views, as a strict near-starvation diet gradually brings her nearer to a more recent ideal.

It’s a really interesting exhibition; if I’ve piqued your curiosity, there’s some further detail available at the museum’s own site, in English.

The museum isn’t JUST its special exhibitions, of course – the regular galleries are, as I said, crammed to the gills with paintings you’ve probably seen in art history books and works by people whose names you know. It was interesting to look at all those Rubens works together and think that once upon a time, someone built like me would’ve been considered smoking hot rather than constantly reminded how nasty I am for being a bigger girl. It’s a bit liberating; I hope I can keep a little of that and bring it home with me.

By this time we’d seen…oh, maybe half the museum, and I seriously think we could have stayed all day, just taking everything in – but we did have places we needed to be, and so not without a little regret we turned in our audio guides and set forth for Schonbrunn Palace.

Schonbrunn was the Habsburg summer palace – it’s where folk like Maria Theresa and Franz Josef went when they wanted to hit the cottage, so to speak. These days it’s right on one of the subway lines; you can literally hop off, cross the street, and be right there, taking in a first view of that casual summer flavor.

Well, all right, for certain varieties of “casual.”

Vienna is home to two Habsburg palaces, and I think in general if you were only going to tour one of them it would be the other – but this one had an interesting package deal that combined admission with dinner and a little concert. Sure, why not? So here we were, picking up our tickets at the Orangery, a little building off to one side of the entrance.

As it happens, our concert was not to be there today, but in the Grosse Gallerie; more on that a little later. Tickets in hand, we set off to tour the palace itself and its grounds.

And, you know, just a modest little summer place, right?

Honestly, there is something in Baroque style that drives it with remarkable swiftness toward self-parody. Did you know, for instance, that they have a real Roman ruin there?

…Because that is totally a legit Roman ruin and not just a mishmash of any old vaguely Romanesque thing we could find, right? Right?

Okay, okay, I snark. But it was just a bit hilarious how far over the top these gardens were. Kind of lovely, yes, but dang, imperial folks:

As with many a stately home in England, the grounds are both open to the public for warm-weather ambling about and monetized within an inch of their leafy raked-gravelled lives; everywhere near the entrance are industrious folks selling ice cream and offering rides on a trainlike vehicle that seemed popular with small people, and some of what seem like they ought to be the choice gardens one must pay to enter.

Still, it’s a pleasant place to go walking on a cool sunny Spring afternoon – even if the aforementioned gravel IS of a particularly evil vaguely triangular variety that insisted on creeping into my sandals and forming tiny, insidious caltrops. I wonder if Franz Josef ever took a break to wander here, taking a rare chance to think of roses and fountains instead of business. Perhaps he was too devoted to his calling for that? I suppose I’ll never know.

The interior of the palace is hot indeed, both from the crush of the ubiquitous tour groups and from the inconvenient fact that air conditioning had yet to be invented. (Central heating, though, after a fashion: many rooms sport Bavarian ceramic stoves of majestic proportions, stoked from behind by specially-tasked servants via a network of passages in the walls.)

Franz Josef and his wife Elisabeth had their own rooms, here – perhaps not so uncommon as we think, once, but here they feel like a sign of the vague dysfunction that seems to have haunted their marriage despite Sisi’s Princess-Diana public appeal. His rooms are stately, dark, even a bit Spartan by imperial standards; the iron bedstead and the prayer bench speak of a man devoted to his duty. The upright Emperor, I catch myself thinking. Responsibility to a fault, for all that those portraits of his wife speak of his love for her.

Anyone could arrange an audience with the empire’s foremost civil servant: you waited in a grand red room for your name to be called, you went in and spoke your piece, and then eventually the Emperor would incline his head, saying what a pleasure it had been, and the audience would be over.

I wonder very much what kinds of things they asked for. His people.

Sisi’s rooms, by contrast, are dainty and feminine in that lush Baroque way; here she would spend literal hours on her toilette, particularly her infamous mane of gorgeous dark hair. They face the rose garden outside; the breeze in the summer must have been heavenly. She was, they say, a truly legendary beauty; it seems a strange match for a man with such sober habits. But then, I suppose some of us do that – reach out to catch and hold a being whose presence we crave as much for the yawning gulf of difference between us as for any other trait.

The rest of the palace hearkens back to earlier eras still; you can still feel some of the influence of Maria Theresa here amid all the gilding and curlicues and baroque notions of chinoiserie. Even in architecture she is formidable. (I have a vague notion in my mind of her on a movie poster, with some wag laying a slogan at her feet: “Sixteen children. Zero fucks.”)

Eventually the time came for the evening’s entertainment to begin; we made for the little restaurant just left of the main entrance and found every table laid with white tablecloths and neatly-centred vases of flowers. Waiters stood by, a little unnervingly attentive. Time for dinner.

We ordered a glass of wine each and waited as other diners filed in. These dinner-and-concert packages are touristy affairs, but in Vienna this seems to mean something a bit different from what I normally imagine – well-heeled-looking folk largely of my mom’s generation, chatting in a mix of English and German about this and that with a hearty helping of folk speaking what sounded a bit like Russian mixed in. (For the second time in as many days I felt relieved about how dark my jeans were. Not properly dressy for a concert under many circumstances, but here, probably enough.)

Dinner is a prix fixe affair: soup, the Tafelspitz beloved of Franz Josef, and an apple strudel for dessert. All rather surprisingly tasty, and coupled with the chance to sit down for a while quite fortifying.

As the dessert plates and coffee cups were cleared, we made our way into the palace once more – and, unlike our tour this afternoon, nobody seemed to mind a quick photo or two without the flash on as we took our seats and watched for the orchestra to file in.

I mean. Look at that room.

The orchestra was small – just a handful of players, mainly strings – but they did quite well; an assortment of popular classics, mainly Mozart and Strauss (of course), mixed with some arias/art songs here and there. It wasn’t completely boilerplate, fortunately (no “Tales from the Vienna Woods,” which I would have thought an easy pitch down the middle), and at least everyone seemed to be having a good time. (The conductor got everyone in on the action by conducting the audience to clap along with a march right at the end, so there was at least a sense of good fun all round.)

Amusingly, the grounds hadn’t quite completely closed by the time the concert started – so early on I got to watch some surprised and delighted random folk outside, peering in through the slats of the blinds on the doors. By intermission, though, everyone had cleared out but the concert-goers, and we got to have a pleasant few minutes looking out over the Habsburg backyard.

(I still haven’t gotten the hang of night photography on this thing, sorry. Here’s us though!)

Eventually, though, the orchestra headed home and so did we; returning back to our hotel to find those same cute little pink bakery bags full of neatly-folded clean clothes. I still feel a bit like part of the problem…but I AM looking forward to clean clothes in Budapest.

Sounds like the Viennese enjoy their Saturday nights as much as we do. Ah well – I’m beat. Good night, partying Austrians; Vienna, I’ll see you tomorrow.

Oh – and here’s a random bonus snap of one of those cute street lights. These were installed as part of Eurovision, apparently, but everyone liked them so much they’ve kept them around.