Our final full day in the Czech Republic dawned bright and cool, and we set out with a plan: to try for a non-hotel breakfast at the recommended-by-the-food-tour-folks Cafe Savoy, over in Prague’s Little Quarter. This would, we knew, demand some careful timing, since the other priority for the morning was to visit Prague Castle, and we hoped to beat some of the numerous tour groups to the punch (as much as possible anyway.)

So it was that we found ourselves outside the cafe several minutes before it opened, in the company of a few early-morning businessfolk and a handful of people who had the look about them of tourists like us. After a few minutes, a young fellow in kitchen whites emerged to set out baskets of pansies and a waiter in a straight-up tuxedo (sans jacket) began seeing to seating for everyone.

Having heard the French toast here was to die for, and knowing we had a long day ahead of us, we ordered the “French breakfast,” which was…massive.

It also cost about as much as a nice dinner out in Toronto, but since literally everything was delicious as well, somehow I found it difficult to mind all that much.

As we prepared to leave for another round of heavy walking, I stopped to visit the WC – I mention this purely because the area outside said WC is a glassed-in overlook that lets you watch the crew in the pastry kitchen do their thing. While the placement is disconcerting, it’s pretty cool to watch; I recommend having a look if anyone reading this one day happens to go there.

Next stop: Prague Castle. Sort of. We got on the tram heading the wrong way, but fortunately this was readily corrected.

Our travel book made quite a point of saying “Be at St. Vitus’s Cathedral at nine,” but it wasn’t until our slightly delayed arrival at about 9:10 or so that we discovered why: guess where all the tour groups start? …Yeah. Dodging a crew of Russians and at least two of those big crews of Chinese travelers, we bought our tickets and dove for the cathedral entrance.

It’s curious how much the cathedral feels like the heart of the castle. Perhaps this is simply because the castle is no longer a “working” castle: the rooms where the business of governing was actually done are largely empty of furnishings now, waking up only briefly as tourists come to observe them before rolling over and going back to sleep. Once upon a time, kings were crowned here, in the chapel of St. Wenceslas, where the saint’s bones are interred.

St. Vitus himself is here as well, or at least he’s got a reliquary.

There’s also the biggest of the bells in the area, affectionately known as “Zikmund.”

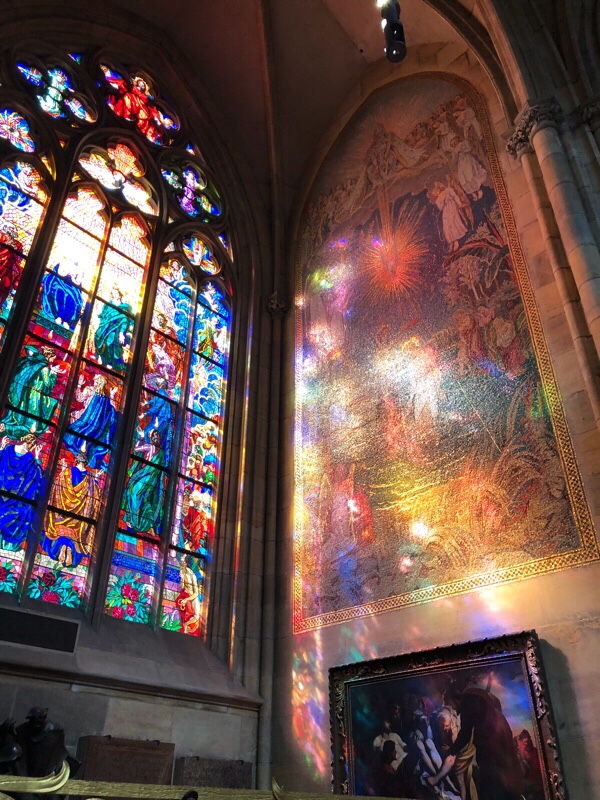

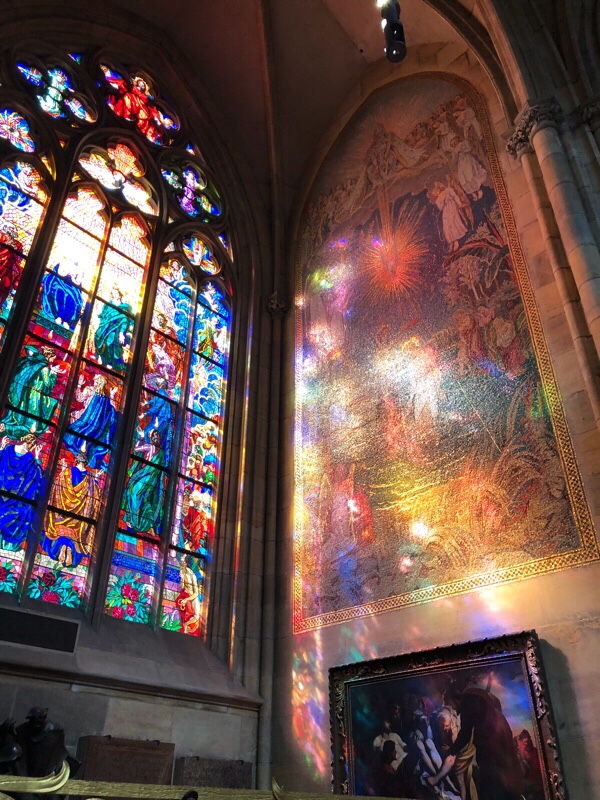

We wandered for a while, taking in the interior (at least as much as was possible around the already-getting-dense crowds.). Here, I’ll share a few views:

The castle interior itself is much simpler: the hefty architecture the Middle Ages tended toward when it wanted to get things done. There is at least one hall that must at one time have been very grand, though:

And there is also the infamous window where the Defenestration of Prague took place:

Quite a lot of madness from such an ordinary-looking window.

We also got a chance to explore “Golden Lane,” a tiny little medieval shopping street that has partly been re-populated with little dioramas of the sorts of shops that filled the place at various points in history and partly with actual shops of ponderous touristiness.

Notable, for me at least, were a rendering of the house of a medium (above) who was quite popular before she was taken in by the Gestapo (as with so many stories like this, it Did Not Go Well) and of a local journalist and intense fan of old films who used to run screenings out of his living room.

I’m…legitimately not sure at this point how many stories I have heard on this trip that seem to end with some variation on “…and then they were taken by the Gestapo.” That always seems to represent the ending when it comes; an uncomfortable full-stop that makes even reading the plaque feel awkward. As though the curator were darting me an awkward glance before moving on with their description.

As we started down the very, very steep hill that pointed us back toward the city centre, we took a pause to tour Lobkowicz Palace. It’s a pretty place, though not over the top extravagant, and visiting it is, for those reading this who played D&D with me, a very VanDeen-y affair. The noble family of the Prince(s) of Lobkowicz lived here, or at least they did until they lost everything in WWII. Then they got it all back, then lost it again under the communists, then got it back again. Now they run a museum that from the sound of it helps them keep the lights on and restorers available for the ongoing maintenance of their vast stashes of goods.

Said stash includes the expected accoutrements of nobility: fine porcelain, silver, paintings of pastoral scenes and engravings by Piranesi. One room contains a collection of paintings of dogs, apparently something of a family fixation; another is populated with images of birds composed largely of the feathers of the bird in question.

It seems the princes were avid followers of the arts in general; the collection also includes a Mozart rearrangement of Handel’s “Messiah” with notes in his own hand, and several scores dedicated to a prior Prince of Lobkowicz who was, I shit you not, Beethoven’s patron. (Things I learned: originally Beethoven planned to dedicate his “Eroica” to Napoleon. However, by the time it was finished, Beethoven was sufficiently unimpressed that he re-dedicated it to the then current prince of Lobkowicz, striking out his earlier dedication with enough force to rip holes in the paper.)

There’s also a painting of the famous defenestration – or rather, what happened shortly afterward. It approaches the situation from a rather different point of view than other accounts we’ve heard to date, however: here, the nobles who were flung out of the window have fled to the Lobkowicz palace for protection, and a family ancestress is shielding them from the angry horde.

The museum also includes an audio guide narrated with rather endearing earnestness by the current…is it still prince? I’m not sure…with cameos from his wife and mother in law. It’s a curious mix of enthusiasm for the collection and impressive manifestation of privilege (Though I did enjoy the anecdote about his father riding a bicycle up and down the grand halls.) At least the desire to preserve all this for future generations seems to be in earnest, and in that I wish them all the best.

Our next stop was perhaps more amusing than classy: Speculum Alchemiae, a slightly cheesy little attraction that sprang up after massive flooding unearthed an honest to god alchemist’s lab tucked away under one of the local houses.

Prague has a tendency to flood: in fact, the level of the city has been raised a few times over the years, and on some much-older buildings the effects of this can be seen. At the old town hall, what is now the cellar used to be the street level, and the former windows are still clearly visible; here, the house where once an alchemist plied his trade sits several feet below the more modern buildings nearby.

The flood unearthed a series of tunnels, one of which led directly to the castle, and in these, supposedly, documents were found that clued everyone in as to what the place once was. These same documents were then used to reconstruct the way the lab may have looked, long ago. It’s a little bit cheesy, but amusing to visit, complete with glassworks, distillery and storage space for a variety of herbs. And hey, it has a secret bookcase.

Mark bought a small clay phial of something that purports to be an elixir of youth, though I suspect its primary virtues may have less to do with revitalizing the flesh than with adding a cute trinket to a bookcase.

Here we paused for a break at our hotel’s “honesty bar,” after picking up a bottle of water at the nearest convenience store, and I surprised myself by downing almost a litre of it without really stopping. I get the sense I am really burning a lot of water just walking around; so far it’s been very humid everywhere we go.

Today was planned as food tour day, so there was time for just one more stop on the way: the Mucha museum, wherein I got to see real life versions of many of those cheap prints seen in college dorms everywhere, including mine. Some of those posters from his Paris period are a LOT bigger than you’re thinking if you’ve only ever seen the prints, as well; Sarah Bernhardt in Medea may not have been quite life-sized, but she sure can dominate a wall.

Here also Mark and I made the happy discovery that there IS some art we can agree on after all – both of us find things to love in Mucha. For him, there is the interplay of forms, I love the use of colour and the swirling, delicate lines; we both love his knack for expressions and symbolism. This is especially fun when looking at some of his work that comes in sets – seasons, flowers, etc.

In the back of the museum is a movie detailing more about Mucha’s life – patronage, contracts, his distaste for society and his patriotic dreams. (We did not make it out to see the Slav Epic this time, but one of these days I should really look into it.) They had some works I’d never heard of before there, let alone seen – like the rather haunting “Star.” Like the Slav Epic, this one has political meaning as well – Mucha painted it in response to hearing about the suffering of the common folk of Russia post-Bolsheviks.

On the one hand, I feel a bit shallow for enjoying works of his that were, essentially, just advertisements; I cannot imagine hanging the average ad that appears on the TTC in my living room. Then again, I may possibly have bought a print of one of his works for myself. Blame my affinity for the “The Moon” card, perhaps.

This done, we headed to the meeting point for our food tour…which we almost missed, even so, after first getting the place right, then thinking we’d got it wrong, then hurrying back to the right one again.

Our guide for the evening was Jan, a guy about our own age who’d studied briefly in the USA and done translation work in the land of high finance before eventually deciding he’d had enough and switching to full-time foodie tourism. Everyone ELSE on the tour was young ladies from the States, most from LA, and most “between jobs,” though I am uncertain quite what that means exactly. This made parts of the experience a bit odd; for instance, I have never been in a room, ever, where people lit up as visibly as the LA girls did when he mentioned the Kardashians.

Ah well. All of us were there because we liked food, at least, so we had that in common. (And here, guys, I am going to do that thing I roll my eyes at people a bit for doing when they do it in restaurants in Canada…I photographed my food so I could share with you. Those of you this will irritate, feel free to skim over this bit.)

Here are sort of the primary take-aways from the entire affair: The Czechs are trying to re-establish a sort of Czech food identity after Communism. Communist life in the Czech Republic was, for most people, more boring than horrific according to Jan. Certainly the regime did a number on food, standardizing recipes down to the weight of ingredients to be used for each dish. Recipes served lots of people at once (the example he showed us served 100) and were the same pretty much everywhere – so if you didn’t like the bread (or whatever) at one place there was very little point in going anywhere else. Restaurants came in four “levels”; I’m not sure if there was much difference between the recipes available at a level 1 vs a level 4, but the part of me that loves going out to St. Lawrence or wherever finds the entire idea just soul-destroying.

Here’s the other important bit, though: as we all know, food is often about comfort for a lot of us. What do we crave when we want comfort? Food we remember from childhood. And what was childhood if you’re Czech and were born within living memory of, say, 1989? That bland gray age of Communist standardization.

This, plus the legitimate desire to create new food that’s still recognizably Czech, results in an interesting mishmash of nostalgia and enthusiasm, springing forth from kitchens staffed mainly by young Czechs. “Notice how young everyone is at all of the places we go,” he commented – and he was absolutely right.

Our first stop was a place called Mysak, where Jan’s mother had taken him as a child were he to get unusually good marks at the end of a term. This was an example of a place that had been family-run for ages and doggedly kept open throughout communism, only for the owner to pass away without anyone to pass the business to shortly after communism fell. A new generation’s picked it up, however, and it is once again a popular, slightly upscale spot. Here we had a petite open-faced sandwich topped with shrimp – an affluent indulgence in a landlocked country – and a kind of cream-filled glazed cruller called a “venecek” that I think I would have eaten my body weight in given the opportunity:

Here we paused for a bit of chat about pricing. There comes a point for everyone, it seems, where the idea of “what something should cost” becomes fixed in one’s mind. Perhaps about fifty or so. In the Czech Republic, this means that for many, “what food should cost” is “what food cost under communism,” so a lot of older Czechs especially don’t visit places like this because the food seems too expensive. There is certainly a kind of Overton window of costs where an amount of money becomes “a lot” to you; for me that’s about 100 dollars, but for Mark it’s rather higher. I wonder how much things like that change within one’s lifetime? I know $20 was once “a lot” to me, and then $50…Who knows, I suppose.

There is no “bank of mom and dad” in the Czech Republic, either: here, the generational wealth gap exists in the inverse of North America. At home, it’s older generations that tend to have money; here, the reverse. Sometimes this means that these older folks will even be resistant to fixing up a crumbling apartment block because doing so will raise rents: there are some buildings where younger tenants are literally waiting for older ones to die in order to conduct repairs.

On our way to the next stop, we poked our heads in at the main post office for Prague. They are very very serious about not taking photographs in there, so I don’t have any unfortunately, but it’s a surprisingly pretty building. It’s also open 24/7, and is the nexus for quite a few bits of Czech bureaucracy. (Another thing I learned today: Everyone has a mailing address here, even the homeless folks – their messages will just go to the post office proper and it’s their responsibility to check them.)

Stop number 2 of our tour was Kantyna, “the palace of meat,” a former Masonic temple turned fancy butcher shop-slash-eatery where you can order meat by weight and have it brought to you. This place is crazy busy, and a number of tables had reservations marked with numbered bones, but the tour group we were with has a special arrangement whereby sometimes they will set up a card table for those who’ve been on the tour. Appropriately to the setting they brought out a tray of pulled pork, dry-aged sausages, latkes fried in pork fat, and steak tartare.

The latter one eats by first vigorously rubbing the toasted bread with a cut clove of garlic; the garlic was pleasingly spicy, much more so than in Canada. I don’t know what causes that, but I wish I could have some to cook with at home!

We also had a dark lager called “Kozel” here. This is the gateway beer in this part of the world, apparently; the lighter stuff that teenaged girls drink. (Still not really my jam, but I figured if there was ever a “when in Rome” sort of occasion this was it.)

On our way to our next stop we learned another interesting factoid: you know that Jewish quarter we visited? There are still some Jews in Prague, but not many: only 1500 or so officially registered, most over 55. This came up because the former Jewish quarter was home to stop number three: Lokal, a small chain with just a few locations that is riffing on the classic Czech pub.

These are trading on the aforementioned communist nostalgia very hard, naturally, which means that walking into one is a bit like walking into the legion hall at first glance: comfortable if spartan-looking seating, a long bar, painted stencilwork on the wallpaper. The “riffing on” element becomes more apparent when you look more closely at the walls: wood paneling that looks very 70s has been gouged with graffiti-like carvings that are lit from behind. A decorative feature, not defacements.

This is because, as we learned on sitting down, the local pub is a place where you go to do two things, mainly: drink, and talk to your friends, largely to complain about all the things in your life that make you crazy. So there’s no music being played (a difference from Canadian pubs I didn’t register at first), and the food on offer is mostly of the “stuff you serve with beer” variety.

Czechs drink a lot of beer. A LOT. Jan showed us a typical beer-ordering card, a long strip with many, many little outlines of mugs of beer on it. When the waitress sees you’re empty, or running low, she’ll come by with another, marking off one of the outlines, unless and until you explicitly say “no more.” At the end of the night you cash out – a procedure Jan referred to as “Czech dim sum.”

How many beers on the average do Czechs have this way? Eight or nine a night, easily.

We had just the one, this time a Pilsner Urquell lager that came from a giant tank under the bar. There are about six of these active in any pub at a given time, and they will go through three tanks in a night, easily. When refill time comes, a tanker truck full of beer pulls up to the pub and fills ’em up, gas station style.

…What do you eat with all that beer? Well, fried cheese is popular; this is served with tartar sauce (?) and tastes about as awesome as fried cheese generally does. There was also a Hungarian-style goulash, and chicken schnitzel served with a warm, vinegary potato salad.

Here we also learned something that might possibly explain why Prague was so much less crowded than I had anticipated: apparently the Czechs love going to the cottage on holiday weekends as much as Canadians do, so a goodly chunk of the city may have been out for a time.

Next stop, a second meat-themed spot, Nase Maso, for a sample of their meatloaf sandwich.

About this, I cannot say much except that it was very tasty, and they have provided us with the recipe, which I may try one of these days when I have people over. We did learn an interesting factoid about the place, though: there is a wine bar nearby, and you can apparently have the butcher shop grill you a steak and bring it over. (I must confess I rather like the idea of summoning a steak like this, though I didn’t get the chance to test drive it. Ah well. On a future trip perhaps.

Onward, again – and outward in this case, to the neighbourhood of Kalin well outside the touristy zones of the city; rough-but-gentrifying, perhaps the closest Torontonian analogue would be the Junction. Here, tech companies have settled in, and a little crop of restaurants trying out new things have sprung up to serve them. As we headed to our first stop here, we passed a lengthy queue; investigation revealed that playing that night was Bobby McFerrin. (There’s a name I haven’t thought of in a while…)

Next stop, Eska, a trendy-looking spot where we were seated “at the chef’s table,” near the kitchen. Here we were treated first to a gin and tonic crafted with an artisanal gin by a local, along with a seriously adorable little amuse-bouche crafted with radish slices and edible flowers:

I love the water-lily look. This was followed by a modern riff on what is apparently a popular Czech campfire dish: “ash potatoes,” which as the name suggests are potatoes tossed into the campfire ashes to roast. Ours were served a bit more elaborately than that, though:

This was a kind of deconstructed baked-potato affair, and it was seriously delicious. As we waited for our next course, we watched the kitchen doing its thing. (Jan commented “They say there are three things you can watch forever: fire, the sea, and other people working.”)

Perhaps he’s right about that; it was weirdly gratifying to watch the kitchen staff as they boiled, roasted, plated…

The next course was mushroom-oriented: a sort of fermented wheat berry risotto-like substance rich with mushroom flavours.

The Czechs apparently not only eat a lot of mushrooms but forage for them regularly as well; all Czech students receive some basic mushroom education in school, and many towns have a sort of mushroom assistance agency that will help you identify the mushrooms you’ve made it back with. These are staffed by “Unabomber weirdo types,” as he put it, but they’re quite knowledgeable, and foraging can be a way to make some extra cash if you know what you’re doing.

Above: “pre-dessert,” a little nibble before we headed out. Whee!

Our final stop for the evening was the Krystal bistro for a traditional Czech dessert: plum dumplings with butter, poppy seeds, and stewed plums, paired with another local artisanal spirit: a walnut brandy. Both dumpling and brandy were lovely: warm and comforting, buttery, fruity density and woody acidity together.

At the end of the evening Jan had some additional gifts to see us off: tram tickets back to the old town, and a Koh-I-Noor pencil for everyone. These are apparently a Czech innovation, too. File that under things I didn’t know, certainly…

By this time we were so full we were more than happy to just head back to the hotel and collapse for the night, thank you. Anyone thinking of going to Prague who likes food, though: go do this. It was a great time, it was delicious, and I’ll be giving them some good internet ratings when I get back to Toronto.

Tomorrow: we head to Vienna.

Good night, Prague. It’s been fun!

(Please enjoy Mark with this painting of chickens.)